Biography

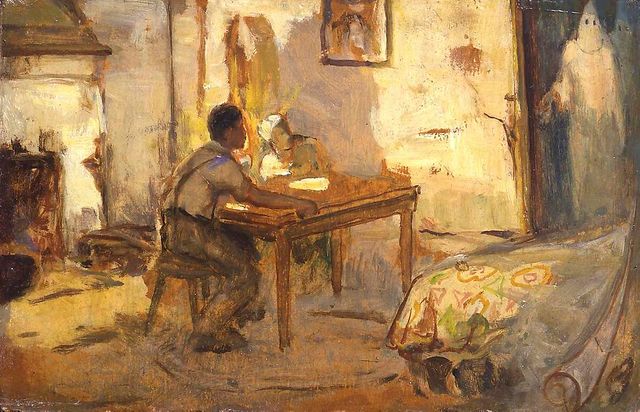

William Edouard Scott, a pre-eminent African American muralist, portraitist and illustrator in the half-century before the civil rights revolution, was born to Caroline Russell Scott and Edward Miles Scott on March 11, 1884 in Indianapolis. Showing precocious talent in drawing at Indianapolis’s Manual Training High School, Scott enrolled in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, graduating in 1909. From 1909 until the eve of World War I, Scott spent much of his time abroad in Paris, where he was mentored by Henry Ossawa Tanner and trained at Paris art schools such as the Academie Julian and the Academie Colarossi. His work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. Tanner’s influence helped spur Scott’s interest in depicting biblical scenes, as well as his skepticism for modernist forms such as cubism and later the Egyptocentric silhouettes of Harlem Renaissance illustrator Aaron Douglass. When he was in the United States, Scott painted murals for schools and other local institutions in the Midwest, particularly in Indianapolis and Chicago. One Scott school mural dedication ceremony that attracted press attention included a musical performance by fellow Indianapolis native Noble Sissle, future co-composer of the epochal black musical Shuffle Along (1921). Scott returned to live in Chicago permanently in 1914. In 1918, he designed the cover art for the November and Christmas 1918 issues of the NAACP journal The Crisis , edited by W.E.B. Du Bois. The covers reflected the two great issues in the black discourse of the day: the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to Northern and Southern cities, and African American involvement in The Great War. At the same time, other compositions of Scott’s venerated the South-based manual labor and technical training ideology of Booker T. Washington. In 1922, Scott married Esther Fulks, a social worker from Charleston, W.Va. As the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s gathered momentum, so did Scott’s reputation. His work was included in some of the Harlem Renaissance’s most important exhibitions, such as the 1927 Negro in Art Week show, the first all-black exhibition of visual art in the United States, and the 1933 Exhibition of the Productions of Negro Artists. In 1928, Scott won a Harmon Foundation Medal, one of the most prestigious awards for “New Negro” cultural workers. In 1931, a year after the birth of his only child, daughter Joan Edaire Scott, William Edouard Scott received a Rosenwald Fellowship to travel to Haiti to paint. Scott’s Haiti paintings did not focus on the island’s illustrious revolutionary history that captivated so many black artists of the period, such as Jacob Lawrence. However, the evocation of the day-to-day life of Haiti’s black peasantry in works such as Scott’s “Haitian Fishermen” helped inspire a widespread artistic turn away from racial uplift and the politics of respectability. Scott, along with other Chicago Renaissance artists, turned toward black working class and folk subject matter; the trend resonated widely among black artists in Haiti and elsewhere in the African diaspora. In 1936, Scott received the National Honneure et Merite from Haiti’s president, Stenio Vincent, for his work. As the Great Depression deepened, spurring Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to subsidize artists, Scott painted murals in parks throughout Chicago under the auspices of the Illinois Federal Art Project. He was also involved in organizing and maintaining Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center, a central hub of black art and cultural politics in the 1940s, frequented by luminaries such as Richard Wright and Paul Robeson, as well as by unsung Bronzeville artists. At the behest of black social scientist Horace Cayton, co-author of Black Metropolis , Scott elaborated on his long-held interest in historical subjects by painting a series of murals and portraits that together recapitulated the triumphs and tragedies of the African American experience from the Revolutionary War era through the Great Migration for Chicago’s 1940 American Negro Exposition. In 1943 his anonymous composition of Frederick Douglass’s appeal to Abraham Lincoln, calling for enrollment of African Americans in the Union Army, was selected as one of seven murals to adorn the new Office of the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C. Scott devoted much time to black education. Embarking on a lecture tour through West Virginia high schools in 1939, Scott stressed the imperative for young black artists (and blacks in general) to remain steadfast and ambitious in the face of racism. In spring 1949, he helped organize and participated in an exhibition of artwork created by black students at Bradley University, including his daughter, Joan Scott. That summer he accepted a summer faculty appointment at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College. Scott’s mural for the Chicago Catholic Youth Organization depicted black and white athletes training together. As his renown grew, Scott was featured in publications such as Color , the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Defender , sometimes being hailed as the foremost Negro artist in America. These features often portrayed Scott, with his small, successful nuclear family, as a paragon of the morals and accomplishments of the post-World War II black middle class. In 1955, Scott fulfilled a long-held desire to travel to Mexico to paint. Mexico had been an inspiration for African American artists for decades; by the early ’50s it was also haven for artists with leftist affiliations fleeing McCarthyism. However, he had to cut the trip short due to health problems. In May 1960, against the backdrop of the rising sit-in movement, Scott presented one of his last major murals, “The Negro in Democracy,” at the South Side Community Art Center. He also remained active at Chicago’s St. Edmund Episcopal Church. William Edouard Scott died on May 15, 1964, at the age of 84, survived by his wife, Esther Fulkes Scott, and daughter, Joan Scott Wallace.

Track William Edouard Scott

Get notifications when works come to auction, and access market analytics

Create Free AccountAlready have an account? Sign In

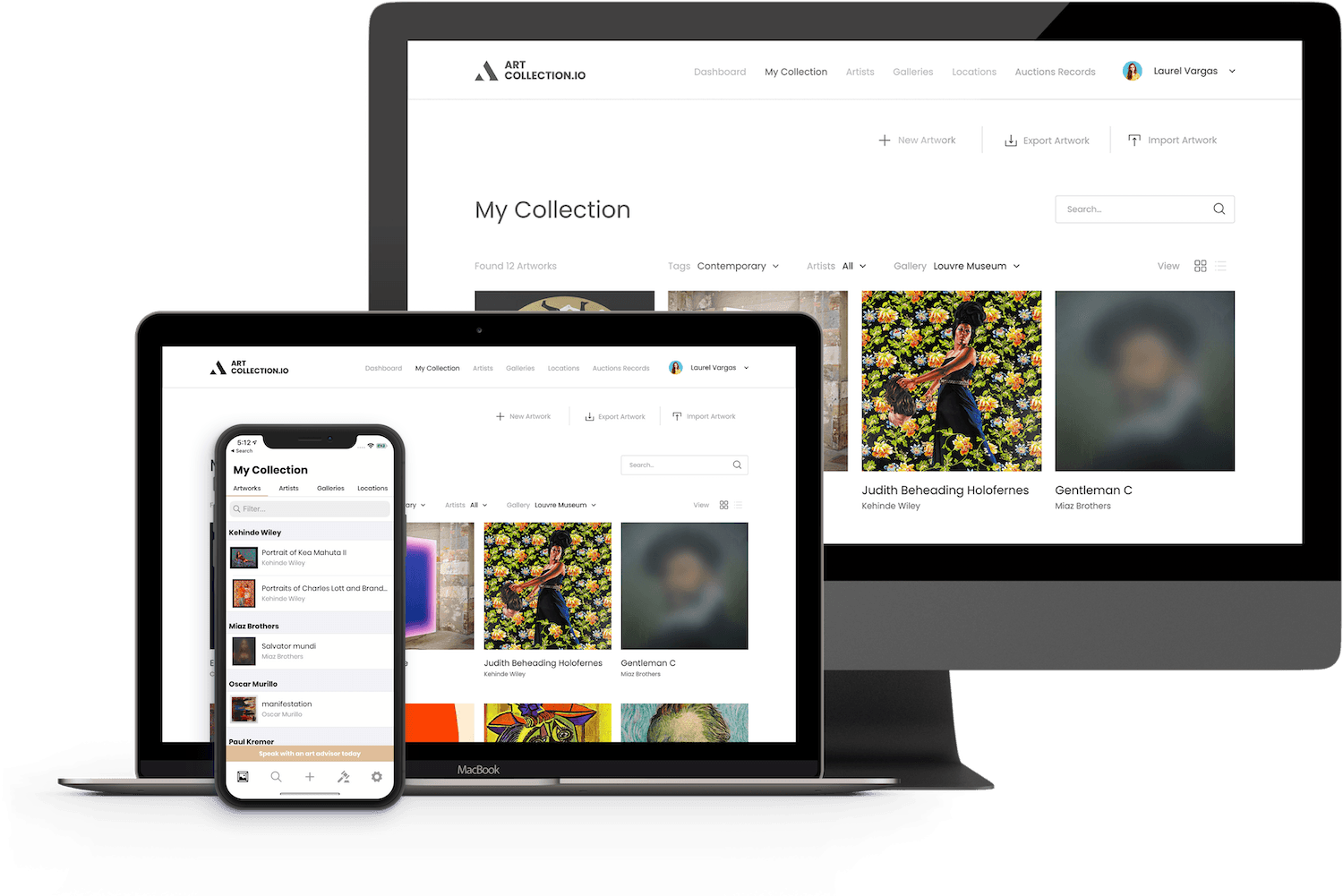

Available on any device, mac, pc & more

ArtCollection.io is a cloud based solution that gives you access to your collection anywhere you have a secure internet connection. In addition to a beautiful web dashboard, we also provide users with a suite of mobile applications that allow for data synchronization and offline browsing. Feel confident in your ability to access your art collection anywhere around the world at anytime. Download ArtCollection.io today!

Biography

William Edouard Scott, a pre-eminent African American muralist, portraitist and illustrator in the half-century before the civil rights revolution, was born to Caroline Russell Scott and Edward Miles Scott on March 11, 1884 in Indianapolis. Showing precocious talent in drawing at Indianapolis’s Manual Training High School, Scott enrolled in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, graduating in 1909. From 1909 until the eve of World War I, Scott spent much of his time abroad in Paris, where he was mentored by Henry Ossawa Tanner and trained at Paris art schools such as the Academie Julian and the Academie Colarossi. His work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. Tanner’s influence helped spur Scott’s interest in depicting biblical scenes, as well as his skepticism for modernist forms such as cubism and later the Egyptocentric silhouettes of Harlem Renaissance illustrator Aaron Douglass. When he was in the United States, Scott painted murals for schools and other local institutions in the Midwest, particularly in Indianapolis and Chicago. One Scott school mural dedication ceremony that attracted press attention included a musical performance by fellow Indianapolis native Noble Sissle, future co-composer of the epochal black musical Shuffle Along (1921). Scott returned to live in Chicago permanently in 1914. In 1918, he designed the cover art for the November and Christmas 1918 issues of the NAACP journal The Crisis , edited by W.E.B. Du Bois. The covers reflected the two great issues in the black discourse of the day: the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to Northern and Southern cities, and African American involvement in The Great War. At the same time, other compositions of Scott’s venerated the South-based manual labor and technical training ideology of Booker T. Washington. In 1922, Scott married Esther Fulks, a social worker from Charleston, W.Va. As the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s gathered momentum, so did Scott’s reputation. His work was included in some of the Harlem Renaissance’s most important exhibitions, such as the 1927 Negro in Art Week show, the first all-black exhibition of visual art in the United States, and the 1933 Exhibition of the Productions of Negro Artists. In 1928, Scott won a Harmon Foundation Medal, one of the most prestigious awards for “New Negro” cultural workers. In 1931, a year after the birth of his only child, daughter Joan Edaire Scott, William Edouard Scott received a Rosenwald Fellowship to travel to Haiti to paint. Scott’s Haiti paintings did not focus on the island’s illustrious revolutionary history that captivated so many black artists of the period, such as Jacob Lawrence. However, the evocation of the day-to-day life of Haiti’s black peasantry in works such as Scott’s “Haitian Fishermen” helped inspire a widespread artistic turn away from racial uplift and the politics of respectability. Scott, along with other Chicago Renaissance artists, turned toward black working class and folk subject matter; the trend resonated widely among black artists in Haiti and elsewhere in the African diaspora. In 1936, Scott received the National Honneure et Merite from Haiti’s president, Stenio Vincent, for his work. As the Great Depression deepened, spurring Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to subsidize artists, Scott painted murals in parks throughout Chicago under the auspices of the Illinois Federal Art Project. He was also involved in organizing and maintaining Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center, a central hub of black art and cultural politics in the 1940s, frequented by luminaries such as Richard Wright and Paul Robeson, as well as by unsung Bronzeville artists. At the behest of black social scientist Horace Cayton, co-author of Black Metropolis , Scott elaborated on his long-held interest in historical subjects by painting a series of murals and portraits that together recapitulated the triumphs and tragedies of the African American experience from the Revolutionary War era through the Great Migration for Chicago’s 1940 American Negro Exposition. In 1943 his anonymous composition of Frederick Douglass’s appeal to Abraham Lincoln, calling for enrollment of African Americans in the Union Army, was selected as one of seven murals to adorn the new Office of the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C. Scott devoted much time to black education. Embarking on a lecture tour through West Virginia high schools in 1939, Scott stressed the imperative for young black artists (and blacks in general) to remain steadfast and ambitious in the face of racism. In spring 1949, he helped organize and participated in an exhibition of artwork created by black students at Bradley University, including his daughter, Joan Scott. That summer he accepted a summer faculty appointment at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College. Scott’s mural for the Chicago Catholic Youth Organization depicted black and white athletes training together. As his renown grew, Scott was featured in publications such as Color , the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Defender , sometimes being hailed as the foremost Negro artist in America. These features often portrayed Scott, with his small, successful nuclear family, as a paragon of the morals and accomplishments of the post-World War II black middle class. In 1955, Scott fulfilled a long-held desire to travel to Mexico to paint. Mexico had been an inspiration for African American artists for decades; by the early ’50s it was also haven for artists with leftist affiliations fleeing McCarthyism. However, he had to cut the trip short due to health problems. In May 1960, against the backdrop of the rising sit-in movement, Scott presented one of his last major murals, “The Negro in Democracy,” at the South Side Community Art Center. He also remained active at Chicago’s St. Edmund Episcopal Church. William Edouard Scott died on May 15, 1964, at the age of 84, survived by his wife, Esther Fulkes Scott, and daughter, Joan Scott Wallace.

Track William Edouard Scott

Get notifications when works come to auction, and access market analytics

Create Free AccountAlready have an account? Sign In

Available on any device, mac, pc & more

ArtCollection.io is a cloud based solution that gives you access to your collection anywhere you have a secure internet connection. In addition to a beautiful web dashboard, we also provide users with a suite of mobile applications that allow for data synchronization and offline browsing. Feel confident in your ability to access your art collection anywhere around the world at anytime. Download ArtCollection.io today!