The top three recent art controversies: Forgeries, out-of-this-world profits, and a missing masterpiece

Every once in a while, the art world is shaken by heated controversies swarming around its top players. At the top, few have access to privileged information and take part in extremely lucrative transactions falling under the umbrella of a gallery, auction house or reputable dealer, and usually supported by reliable, but not always definitive, provenance and authentication records. The top three, and most recent, art scandals include a New York gallery director allegedly unaware that she was selling forged paintings, a Swiss businessman acting as an art advisor, dealer and seller, and finally, a Da Vinci painting hidden from the public that has also raised polarizing opinions about its authorship.

A forgery scandal: The Knoedler fakes

Who should verify the authenticity of an artwork, the seller or the buyer? And is art authentication a bulletproof science? Well respected galleries would seem like the best option to acquire “authenticated” artworks but even the most privileged galleries have been caught in forgery scandals. The latter was evident in the Knoedler fakes: a large-scale case of fraud unleashed in 2011, involving some of the top players, in the epicenter of the Contemporary art world, New York City.

Beginning in 1994, the Knoedler & Co gallery, an Upper Eastside gallery once owned by Michael Hammer under the direction of Ann Freedman, sold fake works by artists such as Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko and several others for an estimated $80 million. It began when Glafira Rosales, a Long Island art dealer, brought the first of 40 undocumented and previously unknown works of art by several Abstract Expressionists to Knoelder. In 2013, during the trials surrounding the scandal, Rosales confessed that the paintings were fake and blamed her ex boyfriend, José Carlos Bergantiños Diaz (now a fugitive in Spain), for coercing her to continue the scheme. “They were the Bonnie and Clyde of the art world,” Barry Avrich exclaimed to The New York Times after interviewing Bergantiños.

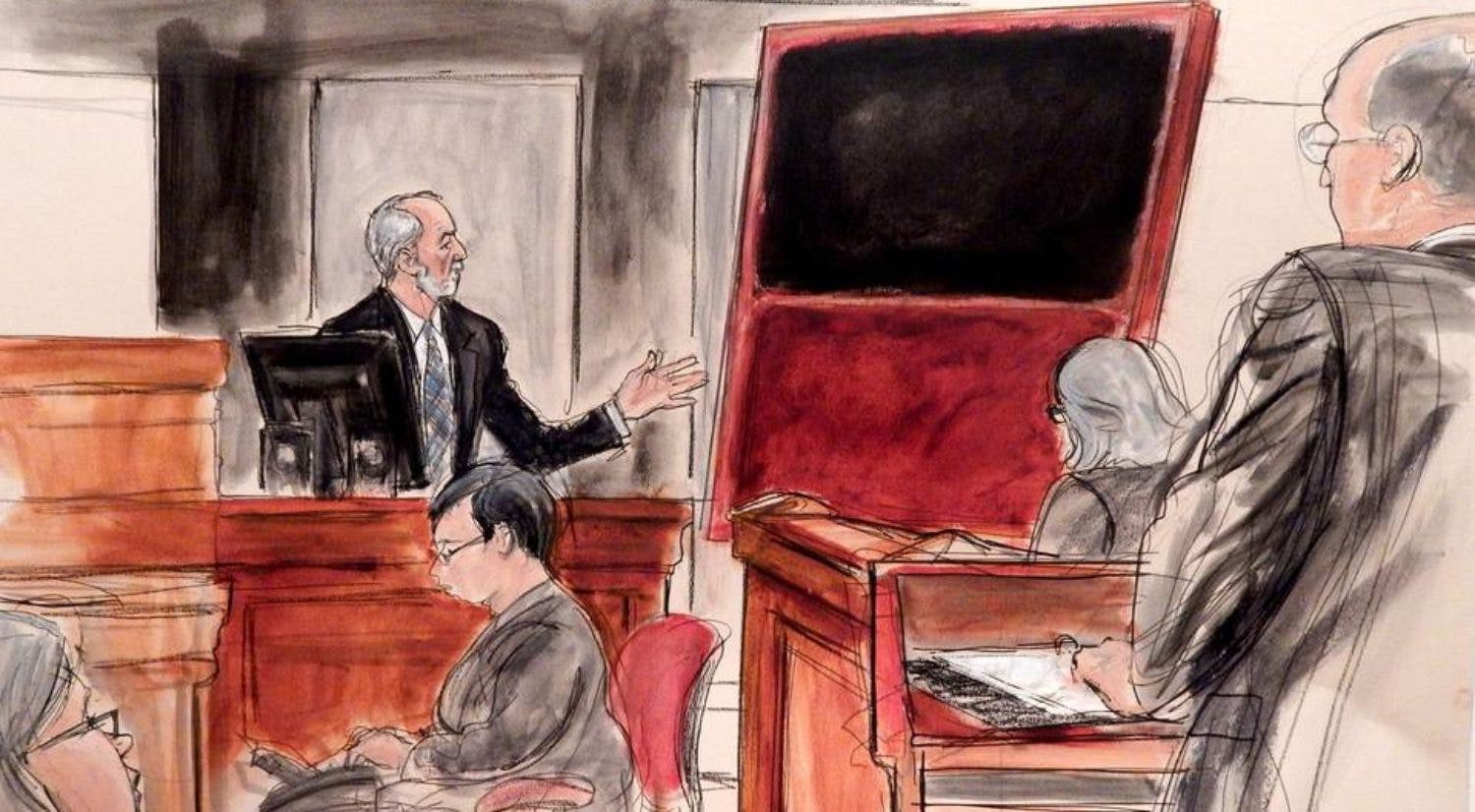

To this day, Freedman sticks by her initial statement that she did not know that the works Rosales sold to her were fakes, and were actually produced by Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese-born artist previously based in Queens and now conveniently located in China. During the transactions, Rosales argued the the paintings were owned by a wealthy Swiss owner, an alleged Mr. X, who wanted to remain anonymous. A total of ten lawsuits were made against Knoelder with the latest plaintiffs settling in 2019.

Of the cases, Domenico and Eleanore De Sole drove the most media attention and settled in 2016. Not only were the De Sole’s wealthy collectors and patrons of the arts, but Domenico was the Chairman of the Board of Directors at Sotheby's. His connection to the auction house proved that even the most connected and wealthy could hold fakes amidst their millionaire dollar art collections.

The Knoelder scandal shed some light on the authenticity of art and exposed the mixed opinions of scholars, dealers and institutions regarding its validity. Former curator of the National Gallery, E.A. Carmean (who did research for Knoedler), the Rothko scholar David Anfam, and Conservator Dana Cranmer were among those who believed in the legitimacy of the works. However, art authorities like IFAR or the Dedalus Foundation (Motherwell catalogue raisonné) raised doubts about them. Some forensic studies were also conducted which further questioned the paintings’ authenticity. Freedman argues that there were some “interests” behind the suspicions’, and in an interview with The Art Newspaper she stated, these concerns “gave me more fire to be proving better and harder what I believed.” She went on to say, “I have never deliberately done something wrong…It doesn’t mean I haven’t…done things that I would like to take back…mistakes happen.” Certainly mistakes do happen, but this one cost millions of dollars and affected the careers of those involved.

A new documentary, Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art, by filmmaker Barry Avrich explores this scandal. The film was initially released in Canada and is scheduled to be released in the US and Toronto in October. The Art Newspaper reported that the director marvelously managed to capture the opinions and complexities of the characters involved in the case and that it would be a spectacular film worth watching.

The Bouvier affair

Put yourself in the shoes of Russian billionaire, Dimtry Rybolovlev. Now, what would you do if at a 2014 New Year’s party you discovered that you overpaid $22 million for a piece of art that was sold to you by your trusted art advisor of 12 years?

The scandal, turned-legal-battle, started in early 2015 between Dimtry Rybolovlev and Yves Bouvier, the Swiss owner of Natural Le Coultre in Geneva Freeport. The story reveals the blurring lines between the roles of an art dealer, an art advisor, and an international art shipping and storing company. There is an unwritten code between them that includes access to information, discretion, and trust, however, and on more than one occasion, it has been broken. But breaking this code isn’t technically illegal, it’s just frowned upon.

During the 12 years, Bouvier helped Rybolovlev acquire 38 masterpieces for $2 billion. The controversy resides in the fact that Bouvier obtained $1 billion in profits, which most likely came as a result of overcharging his exceedingly wealthy Russian client. To secure profits of such high magnitude, Bouvier would buy the artworks himself and then immediately resell them to offshore companies that acted as the initial sellers. Not only did Bouvier have a network of dealers he communicated with, he had access to selective art market information, mainly through his shipment and storage company that had facilities in Singapore, Luxemburg, and Geneva. Bouvier stood by his claim that he acted as a dealer and not as an advisor, while the Russian declared that Bouvier was acting as an advisor and agent that obtained a fee for his services.

The New York Times reported that a recent turn of events resulted with the case being dismissed in Monaco for wrongdoings in the process. However, there are still lawsuits pending for both Bouvier, in Geneva for art fraud, and Rybolovlev, in Monaco for corruption. The latest development is only a chapter in a long series of lawsuits contaminating international courts around the world including Singapore, Paris, New York and Geneva. Even if Bouvier has not been found guilty for these charges, his business has certainly suffered. In 2017, he sold Natural Le Coultre and, in that same year, he put his freeport in Singapore on the market. While he is still co-owner of Le Freeport in Luxembourg and maintains some art business, it seems as though the discretion clause that was once held in such high regard, no longer remains.

In this long-lasting controversy, Bouvier insists that like any other art dealer, he was entitled to charge Rybolovlev whatever he was willing to pay, referring to it as “a commercial game.” And outside of the courtrooms, one of the more publicized incidents of the “commercial game” Bouvier liked to play unfolded in 2017 when the Salvator Mundi, which was once sold to Rybolovlev by Bouvier (who first bought it in 2013), obtained a $250 million profit at an auction. Rybolovlev's daughter was present at the auction and updated her father on the multimillion dollar bids. One of Rybolovlev’s representatives later said to artnet NEWS that “This is a welcomed development for the Rybolovlev family trusts as we undertake legal proceedings to address the shocking alleged fraud committed by Bouvier who deceived the family, all while pretending to be a friend and advisor.” While the so-called “unwritten code” has no legal merit, the damage that comes from the manipulation of the “commercial game” will prevail and continue to make headlines.

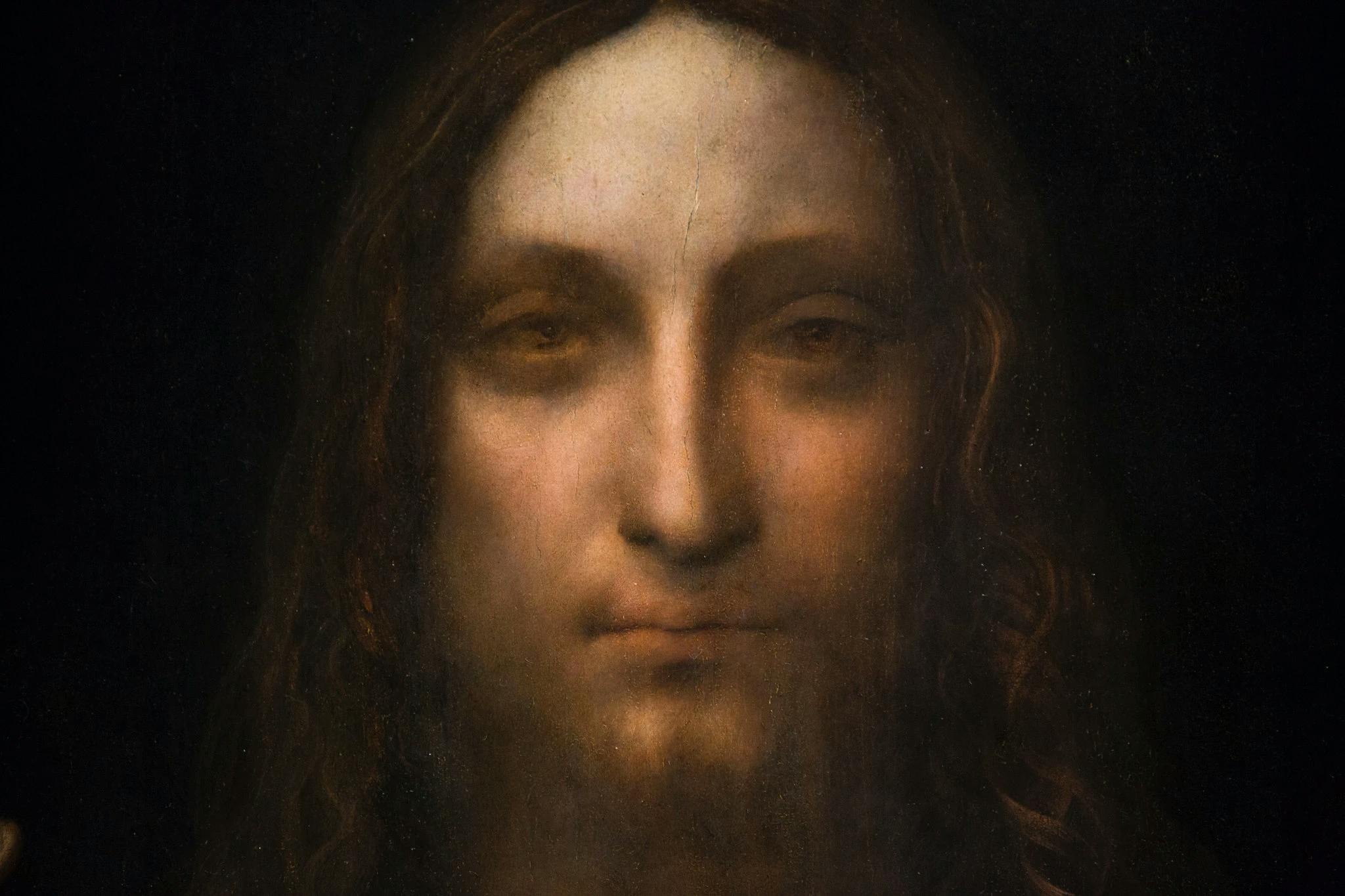

Salvator Mundi: the unanswered questions behind the most expensive painting

How is it that the authenticity of the most expensive painting ever sold is so controversial and up for debate? As mentioned, in 2017 the Salvator Mundi, created around 1500, was auctioned at Christie's for an astonishing $450 million to a “mystery buyer” who was later revealed to be the Saudi Arabian Prince, Prince Badr, who allegedly made the purchase on behalf of Abu Dhabi’s department of Culture and Tourism. However, later developments uncovered that he was only acting as a proxy for the Saudi Arabian Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman.

Since the sale, the exact location of the painting remains unknown. At first it was supposed to be a gift to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, but its unveiling was postponed and eventually, canceled. Tim Harford mentioned that at one point the painting was believed to be on a yacht while others asserted it was waiting in storage in Switzerland. The Washington Post relayed the most recent updates that the Saudi Minister of Culture revealed the Kingdom’s desire to open a new museum to house this painting and until then, it will remain in storage. These plans are part of a multibillion-dollar Saudi strategy to turn the country into an international art destination.

The New York Times reported that the Saudi Crown Prince may not be the painting’s first royal owner. Two similar works were listed in the inventory of the collection of King Charles I of England after his execution in 1649. However, the painting disappeared from the historical records in the late 18th century but then resurfaced in 1958 when it was auctioned at Sotheby's for around $125 at that time. And in 2005, art dealers Robert Simon and Alexander Parish bought the piece for $1,175, under the impression it was made by a disciple of Leonardo Da Vinci. Given its terrible condition, the work was extensively restored by Dianne Modestini, who spent six years with the piece, and only after its restoration was deemed as a real painting made by Da Vinvi himself.

In the timeline of the piece that led up to its $450 million sale, the work was held at the National Gallery in London as a part of the Da Vinci originals exhibit, organized in 2011. The exhibition helped solidify its authenticity and create momentum for its final selling price. However, some debate remains among scholars who doubt its validity. For example, Louis Frank, Curator of the exhibition that marked the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death at the Louvre in France, said to The New York Times that “It’s a damaged painting…Much of it is missing, and it has been restored.” Adding that the “Salvator Mundi is a fragment…and the questions are centered around that fragment.” Salvator Mundi has also been requested on loan to the Louvre but was never approved; there is speculation that the exhibition’s curators intended to label the work as they saw fit, which could have affected its value and importance. Additionally, artnet NEWS discussed how Frank Zöllner, the author of a definitive catalog of Da Vinci’s work, repeatedly questioned the work’s status as an autograph painting. Furthermore, Ben Lewis's book, The Last Leonardo: the Secret Life of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, that also held an excerpt in The Times, UK, gathered several polarizing opinions regarding the authorship of the piece.

While the piece remains hidden from the world, we continue to discuss and contemplate its authorship and validity, and hope that it remains in the constant care and maintenance it requires for preservation. And when the piece reappears, it will most likely be held in a new Saudi Museum with strict access and eligibility for examination.